The Desert

on imagination

As an interlude to Responsibility, a detour through the desert…

I went out as a child into the garden, and it was a terrible place to me, precisely because I had a clue to it: if I had held no clue it would not have been terrible, but tame. A mere unmeaning wilderness is not even impressive. But the garden of childhood was fascinating, exactly because everything had a fixed meaning which could be found out in its turn. (G. K. Chesterton)

None of them ever forgot Roxaboxen. Not one of them ever forgot. (Alice McLerran)

We used to have a garden shed in our backyard. Neglected by its previous owner, it received little more from me in the way of tender love and care. When spring finally sprung—for us, in the third week of April—I had mercy on that shed and demolished it. In the weeks leading up to the demolition, I had some pretensions about putting (perhaps even building) a new shed in its place, or expanding our modest patio and calling it a veranda, or gifting the plot to the land-hungry gardener who also happens to be my wife. Like so many pretensions, these bore no fruit.

For no sooner was the shed removed from the premises than the square of dirt upon which it had stood was put to the very serious and important use of play. Our daughters hauled rocks from the yard, pried up bricks from the patio, recovered sea-shells from last summer’s beach trips, and brought all these materials to the roughly-six-feet-by-six-feet plot upon which the garden shed had stood. With these materials, they built a place. Only it was no place they had ever actually visited. Ignorant of this, I simply asked what they had made, if it was a castle or our house. To which they answered, with the simplicity of the self-evident: “It’s a Roxaboxen.”

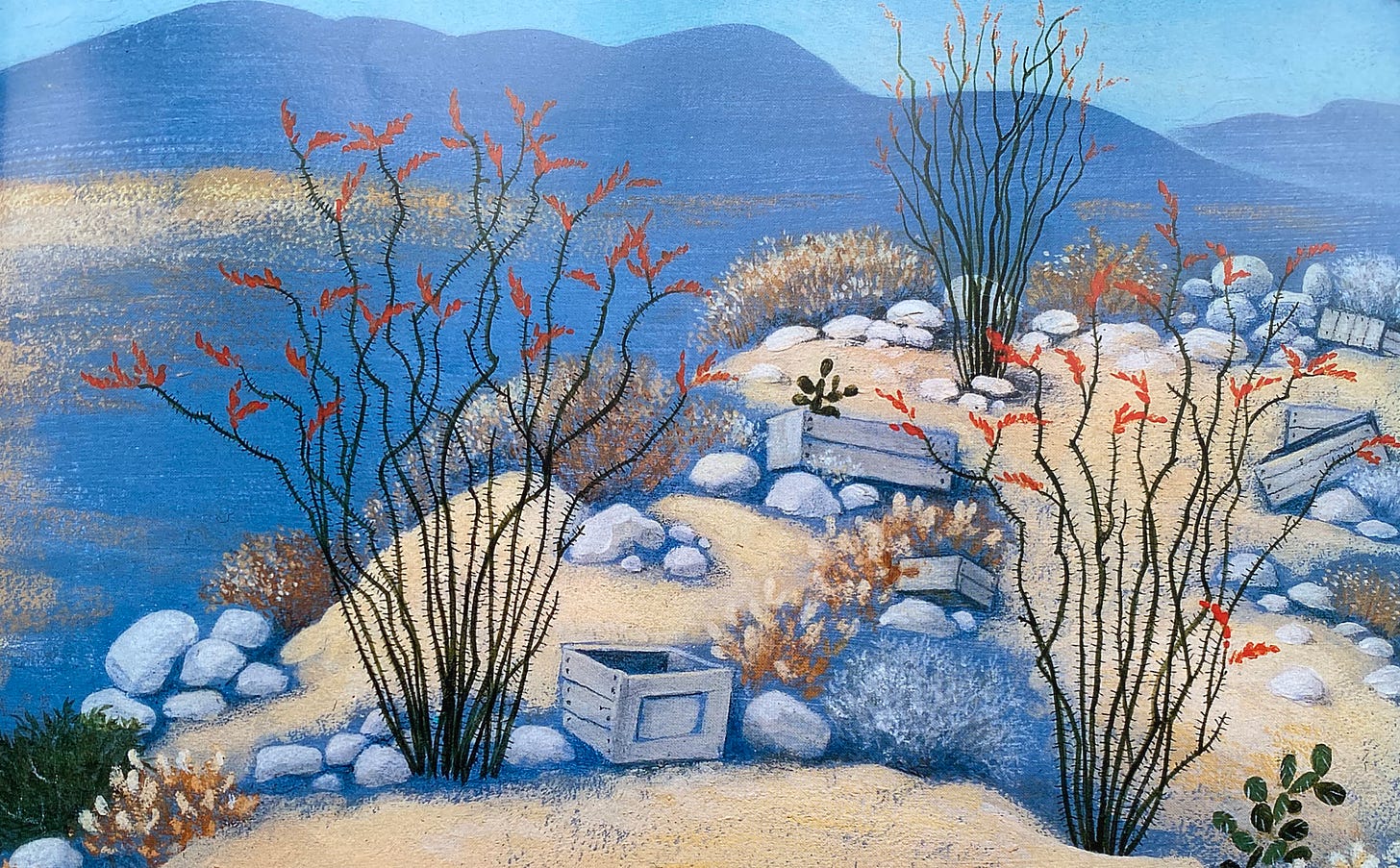

Roxaboxen is Alice McLerran’s 1991 story, beautifully illustrated by the legendary Barbara Cooney, of a rocky hill in the desert and the group of children who transform it into a place to play and to live. Roxaboxen is “a special place.” In Roxaboxen you can find buried treasure; you can eat all the ice cream you want; you can drive a car or ride a horse; you can build a home for yourself out of white stones or, if you are clever and have an eye for it, out of desert glass—“bits of amber, amethyst, and sea green: a house of jewels.” But best of all, you can always return to Roxaboxen; no matter the seasons changing and years passing by, Roxaboxen is always waiting, Roxaboxen is always there.

“The task of the modern educator,” writes C. S. Lewis in The Abolition of Man, “is not to cut down jungles but to irrigate deserts.” I submit that this task is not an inherently modern one, although the pursuit of that task has taken on a heightened urgency in the modern era. The fundamental task in building a child’s imagination is not the tending of growing or already-grown things (although that is itself a necessary task, and one that will occupy the vast majority of time and effort in educating a child). No, the fundamental task in building a child’s imagination is the preparation of the soil so that it can sustain life. In a word, the irrigation of the desert. And why is this? Because a desert is what the child’s imagination is. We do not arrive in this world with knowledge or images or narratives already installed; only once we begin living, feeling, seeing and hearing, out here in the real world, do we begin to accumulate those treasures.

Writing in 1943, Lewis identifies the “pressing educational need of the moment” as the inculcation of “just sentiments”; this, he argues, is the proper antidote to the poison of emotional propaganda that befogs and befuddles the contemporary child. Training of the emotions, of sentimentality, of right feeling—this was the order of Lewis’s day. For our day, however, the order must be for those things which exist prior to the response, prior to the right (or wrong) sentiments. Namely, the objects of those sentiments; the “stuff” of imagination, in other words, those images and episodes and figures and forces which swirl about inside of us and give shape and color to how we see ourselves and the world. All of which is not to imply that the difference between the children (and adults, I suppose) of Lewis’s day and ourselves is that they had imagination and we do not. For the capacity is still there: the difference is with what we have filled it.

It is a simple fact of history, Lewis notes, that “all teachers and even all men…believed, in fact, that objects did not merely receive, but could merit, our approval or disapproval, our reverence or our contempt.” For Lewis, it went without saying that certain of those objects were common goods. You and your neighbor each knew what they were; your children knew what they were; your main task, then, was to train the proper response to those objects, not to generate an awareness of those objects in the first place. Note well the references throughout Abolition of Man to the thinkers and texts of the Tao; in the space of one paragraph, for example, he lists the following without any introductory or supplementary information: Augustine, Aristotle, Plato, the Rta of Hinduism, and Wordsworth. Lewis exhorts educators to instill the power to respond properly in sentiment to these objects; he can happily assume that they are already doing their part to instill the power to know these objects intellectually.

And the same holds true, I think, for imaginative purposes. It benefits us little to inculcate just sentiments about the world of imagination if that world has nothing in it to be sentimental about. That world has to be populated with good things: the things of “flame and adventure,” in Chesterton’s apt phrasing; the things of hearth and home; and the things of Wordsworth’s “first-born affinities that fit our new existence to existing things” to which Charlotte Mason assigns such primary importance. And it must be populated speedily and without delay—the desert can, after all, be a location of temptation.

But it is also a location of wonder. Roxaboxen is by no means unique for its ability to power and populate a child’s imagination. That is, after all, the singular gift and purpose of picture-books, story-books, children’s literature—call them what you like. Namely, to give a child the stuff she needs to build a world for herself; the stuff she needs to build bridges and roads from her world into the worlds that surround her, the world of sister and mother and father, the world of trees, of birds, of flowers; and even the stuff she needs to build a boat to cross the wonderfully vast ocean that roars betwixt her world and the world of God and his angels.

It could be mere happy coincidence that Roxaboxen has been both a highly effective agent in the development of our daughters’ imaginations and it is a story that takes place in the desert. Neither the children nor their parents have sat down to read Roxaboxen with the express intention of communicating the parallel between the story on the page and the world inside our heads—that just as the children in the book turn a dusty desert hill into a place of fun and games and speeding-tickets and a dead lizard, so do we transform the rocky world of our minds and hearts into a garden of well-tilled earth and well-rooted plants.

In retrospect, I should not have been in the least surprised to hear in answer to my question about the rocks and bricks and shells: “It’s a Roxaboxen.” It is obvious that Roxaboxen is perfectly illustrative of the trait which indelibly marks a book as “good for irrigating deserts.” Namely, that it is a story told with no condescension and no slyness—no winks or nods to the adults in the room that it is “just” a story, that its characters are “just” pretending, that its unlimited supply of ice cream is “just” a happy fiction. A story told, instead, with such calm dignity and an assured matter-of-factness in its detailing of the place and events of Roxaboxen that you do not even think to ask yourself whether it is actual or just imagined—any more than a child would ask herself or you that question.

A good story issues no invitation to ask that question. Instead, it invites its reader, its listener, to live the story for themselves. The mark of a good story is that the child cannot help but accept that invitation. As proof of that, I submit to you, not a heap of bricks and stones and shells, but a Roxaboxen.

Credit: Barbara Cooney, illustration to Roxaboxen (HarperCollins, 1991).