“There is no meaningful responsibility without power.” (J. Robert Oppenheimer)

“A fool…built his house upon sand; and the rain fell and the floods came and the winds blew and beat upon that house, and it fell; and great was the fall of it.” (Matt. 7:26–27)

One of the best stories told by legendary American storyteller Jay O’Callahan is “The Little Dragon.” In the story, a little girl named Elizabeth falls into the pages of a book and befriends a little dragon. This dragon is special for two reasons: one, he is the last of the dragons; two, he can’t breathe fire—“he hasn’t got it in him.” Elizabeth teaches him how to breathe fire. “Dragon, I want you to think of fire,” she says; “I see fire in my mind,” he replies—then, upon her command to let out his breath, he promptly breathes forth a flame. And this discovery of fire comes just in time, because the sun has turned blue—by some diabolical trick it is turning to ice! The little dragon, with Elizabeth’s help, must climb to the peak of a mountain and breathe fire into the sun and save the world.

Fire can save the world. This is a tale as old as time. In fact, if we follow the myth of Prometheus, we wouldn’t be telling any tales at all if it weren’t for fire. As William Lynch, S.J., describes in his Christ and Prometheus: A New Image of the Secular (1972): Prometheus is that “legendary initiator of human culture,” the one who “first gave man fire, then the alphabet, then every other resource by which we have been struggling out of darkness.” Moreover, Prometheus is the “great symbol” of the secular project, that “march of mankind,” in Lynch’s words, “in the autonomous light of its own resources, toward the mastery and humanization of the world.”

And this “march” may not be limited strictly to the modern ages of the industrial and the technological—although those certainly have made the most spectacular and expansive inroads toward our mastery of the world. Instead, the “secular project” can be microcosmic: the attempt of each individual, in every place and every time, to accept conformity to “this world” and dimiss that which is above. In that reading, the “secular project” implicates all of us, not just the powerful and enlightened of the modern age. We are all of us Prometheans.

From the divine man receives the tools by which he can survive, then thrive, and then strive for the very heavens. That proposition seems a decent enough description of Christian thought—in general—about the relationship between God (the Creator) and mankind (his creatures). It’s also, of course, a summary of the Promethean myth. The difference is that the Christian version does not end in the rejection of the divine—quite the opposite: the Word becomes flesh and dwells among us; we become God’s children even now; and eventually we will become like unto God himself. But the Promethean legend unfolds differently. The divine rejects the divine before giving certain capacities to humanity, but then the divine is enchained, and humanity is left, quite literally, to its own devices. The prospect of union between God and man is destroyed and the trajectory of history becomes entirely self-enclosed.

How fitting, then, that Paul Johnson concludes Modern Times, his sweeping chronicle of “the twenties to the eighties,” with reference to Alexander Pope’s line, “The proper study of mankind is man.” If the window to the divine is effectively shuttered, then the conclusion that we’ve only ourselves to blame or praise, as the case may be, is only right and just.

Preceding the line “the proper study of mankind is man” in Pope’s “An Essay on Man” is: “Know then thyself, presume not God to scan.” Reviewing the progression of the secular project to date, I think we can say with confidence that it has taken the poem at its word. And one need not go to such vaunted extremes as proclaiming the death of God to dismiss any concerns about his existence or his identity; even if God is alive and well, he can doubtless fend for himself—after all, are not his ways not our ways?

For all the Promethean grandeur of the secular project, can we say with any confidence that its exploits serve as anything but a gloss on these words from Matthew’s Gospel? “A fool…built his house upon sand; and the rain fell and the floods came and the winds blew and beat upon that house, and it fell; and great was the fall of it.”

Considering those words of the publican-turned-evangelist, I initially wrote: “This is what happens when you build your foundation badly.” But that’s not quite right. The judgment being made in that parable is not about the foundation’s technical quality, but the material quality. How we build is anterior to what we build with. I could be the most technically gifted foundation-builder who ever walked the earth, a veritable genius at construction, but setting to work with sand makes me a fool. In fact, the more gifted I am in the technical dimension, the higher a rank I hold among all the other foundation-builders, the greater will be the fall when I squander my gift on shoddy material. All of which is to say: The bigger they come, the harder they fall.

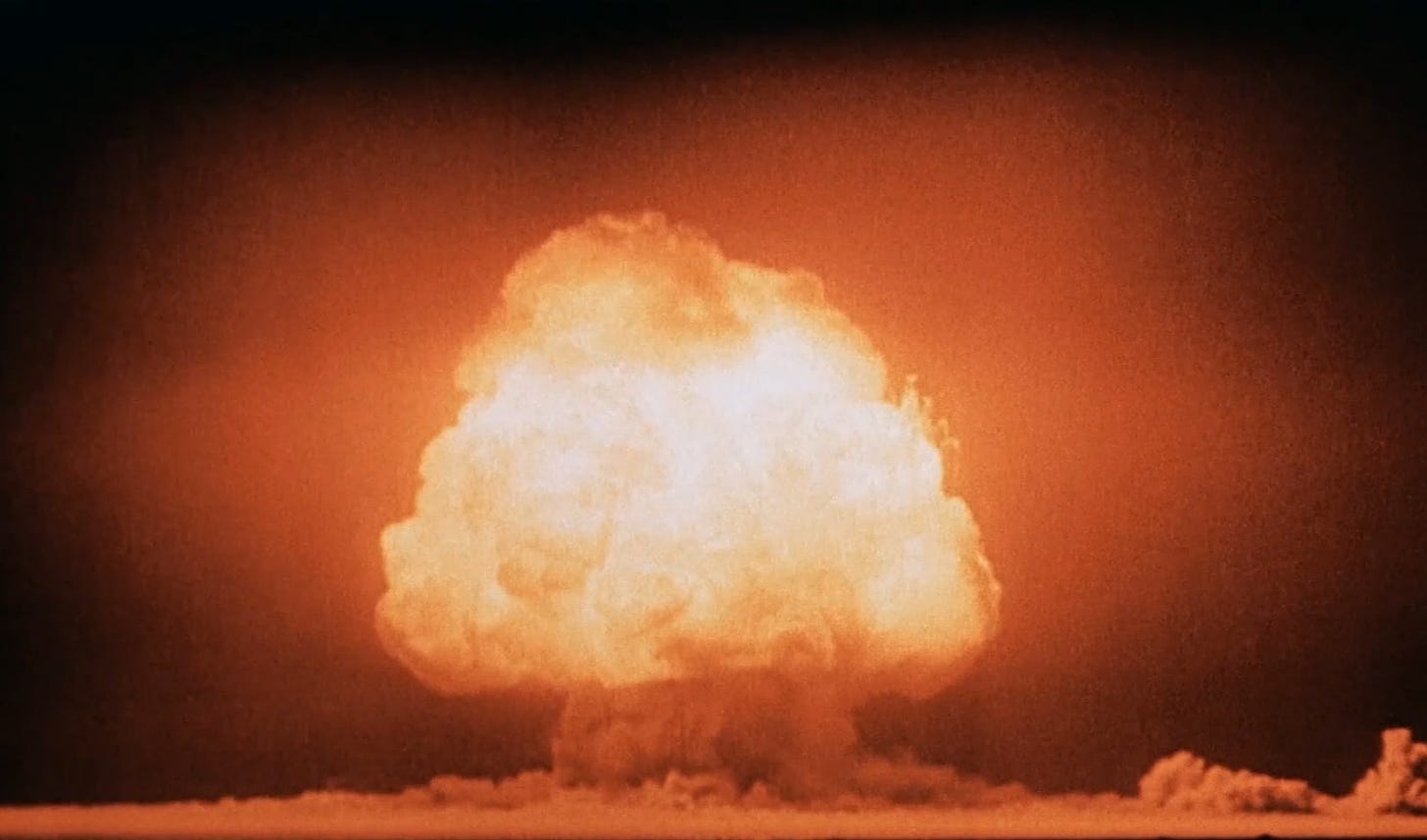

I spent this summer reading American Prometheus, Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s deservedly acclaimed, Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of J. Robert Oppenheimer. “The father of the atomic bomb,” Oppenheimer wrestled “the awesome fire of the sun” to create the weapon intended to end all war. Successful—as we all know—in developing the weapon, he failed to secure the kind of peace which he thought that the atomic era could attain. Instead, the bomb devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki and ushered in a terrible new age of ever-expanding militarization and impending nuclear holocaust. Looking back on his legacy, Oppenheimer famously said, referencing the Bhagavad-Gita, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

American Prometheus has two epigraphs. First, from the September 1945 Scientific Monthly: “Modern Prometheans have raided Mount Olympus again and have brought back for man the very thunderbolts of Zeus.” Second, from Apollodorus: “Prometheus stole fire and gave it to man. But when Zeus learned of it, he ordered Hephaestus to nail his body to Mount Caucasus. On it Prometheus was nailed and kept bound for many years. Every day an eagle swooped on him and devoured the lobes of his liver, which grew by night.”

The sole source for the Promethean epithet, interestingly enough, is that article from Scientific Monthly. Nothing else in the almost-eight hundred pages of American Prometheus indicates that Oppenheimer or his peers themselves thought of their quest after atomic fire in Promethean terms. And yet the epithet is nothing if not apropos. In their Preface, Bird and Sherwin make the identification of Oppenheimer with Prometheus with unmistakable terms:

Like that rebellious Greek god Prometheus—who stole fire from Zeus and bestowed it upon humankind, Oppenheimer gave us atomic fire. But then, when he tried to control it, when he sought to to make us aware of of its terrible dangers, the powers-that-be, like Zeus, rose up in anger to punish him.

The clouds of hyperbole may hang thicker than the facts merit, but the comparison is—as I said—certainly apropos. I thought so after reading the book through; I still thought so after re-reading select portions of the book. But after arriving, Johnny-come-lately, at Lynch’s consideration of Prometheus as the central image for the secular age, I have to qualify that agreement and say: I still think the comparison apropos, but only to a point.

The full title of Bird and Sherwin’s biography is American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer’s triumph was evidently the development of the atomic bomb, the culmination of his ambition, brilliance, and dedication. And what of his tragedy? On the evidence of that paragraph from their Preface, but also from the pacing of the book in general, Bird and Sherwin see Oppenheimer’s tragedy as the ingratitude and humiliation he received at the hands of his country as payment for all his contributions to the national interest and the advance of science. And fair enough—that is a tragedy in Oppenheimer’s life. But it is not the tragedy of that great man. To appreciate the tragedy, we have to delve into “the private experiences of [his] lifetime.” Specifically, we have to look at his education, the formation of his mind, the orientation of his moral compass.

To repeat a reference from Lord of Indiscipline’s inaugural effort, “The Child is father of the Man.” From a very young age, Oppenheimer had instilled in him an unflappable faith in the value of responsibility. Yet, sadly, that sense of responsibility was bereft of any reference to the transcendent. One had a responsibility to oneself, to one’s fellow man in particular and mankind in general, to one’s country, and, perhaps above all else, to mankind’s “moral survival”—the endurance of its capacities to be free and reasonable and good.

Oppenheimer received his primary and secondary education within Felix Adler’s Ethical Culture movement. Adler was a proponent of “deist Judaism,” a pivot away from the biblical religiosity of “the Chosen People” and toward a “non-religion” system of “social action and humanitarianism.” Oppenheimer’s “sensibilities,” in Bird and Sherwin’s words, “can easily be traced to the progressive education he received at Adler’s remarkable school.” The Ethical Culture School was a didactic extension of the Ethical Culture movement in full, and the movement declared that “man must assume responsibility for the direction of his life and destiny.”

For proof that Oppenheimer did indeed take his education from the Ethical Culture movement to heart, one need look no further than his remarks from December 1966:

[Responsibility] is a secular device for using a religious notion without attaching it to a transcendent being. I like to use the word “ethical” here. I am more explicit about ethical questions now than ever before—although these were very strong with me when I was working on the bomb. Now, I don’t know how to describe my life without using some word like “responsibility” to characterize it, a word that has to do with choice and action and the tension in which choices can be resolved.

Compare and contrast those words with these from Adler’s substitution for old-time religion—“the religion of duty”:

Duty may become a religion. I do not say that it must become a religion. A man may pursue the path of duty, looking neither to the right nor to the left, neither above nor beneath, simply intent upon duty and nothing else. But duty may become a religion, if one remembers the cosmic significance of the moral law. A moral or immoral act primarily concerns yourself and your fellowmen. This is the obvious side of it; and there are many who restrict themselves to that side, and say that morality merely concerns men and their relations to one another. But a moral or immoral act has also a wider significance, in as much as it is related to the law, the tendency that obtains throughout the universe.… So, in a much wider sense, a moral act, while it obviously and palpably concerns only one’s self and one’s fellowmen, is yet at the same time an illustration of a universal law in things. The moral law is the highest expression of the same law that binds together in their orbits the celestial worlds. Morality is in essence a law for regulating the attractions and overcoming the repulsions between one human being and others.

Oppenheimer certainly incorporated this moral vision into his own worldview. His ruminations on the legacy of the Manhattan Project are infused with the Adlerian, metaphysically self-enclosed cosmology: “If you were a scientist, you believe that it is good to find out how the world works…that it is good to turn over to mankind the greatest possible power to control the world and to deal with it according to its lights and values.” Yet his personal worldview was not solely derivative. Alongside responsibility he placed discipline as one of the first principles of his philosophy of life:

The fact that discipline, [Oppenheimer] argued, “is good for the soul is more fundamental than any of the grounds given for its goodness. I believe that through discipline, though not through discipline alone, we can achieve serenity, and a certain small but precious measure of freedom from the accidents of incarnation…and that detachment which preserves the world which it renounces. I believe that through discipline we learn to preserve what is essential to our happiness in more and more adverse circumstances, and to abandon with simplicity what would else have seemed to us indispensable.” And only through discipline is it possible “to see the world without the gross distortion of personal desire, and in seeing it so, accept more easily our earthly privation and its earthly horror.”

Another significant development in Oppenheimer’s philosophy of life was the fruit of his relationship with Niels Bohr. Winner of the 1922 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on atomic theory, Bohr had developed his particular interpretation of quantum physics into a worldview that he dubbed “complementarity.” This philosophy essentially held that reality is a mess of contradictions; the only way to understand it is to hold up the opposing forces as complements of one another: “instinct and reason, free will, love and justice, and on and on.” Complementarity solved the inherent tension and contradiction in Oppenheimer’s work developing the atomic bomb: “They were building a weapon of mass destruction that would defeat fascism and end all wars—but also make it possible to end all civilization.” Bohr was adamant that “the contradictions in life were nevertheless all of a piece—and therefore complementary.”

Even before the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer had revered Bohr—so much so that one colleague famously quipped, “Bohr was God, and Oppie was his prophet.” And Oppenheimer himself would call Bohr “his God.” The terminology is solemnly telling, indicative of the tremendous extent to which, in the secular project, the human can absorb the divine into itself. The secular project doesn’t outright abandon the structures or language of the religious instinct. It simply redirects them, substituting the new for the old, I for Thou, sand for rock.

In 1950, Bohr called knowledge the “basis of civilization,” and noted that any increase in knowledge of necessity “imposes an increased responsibility on individuals and nations through the possibilities it gives for shaping the conditions of human life.” Complement this with Oppenheimer’s reflection on his legacy, again from 1966: “There is no meaningful responsibility without power. It may be only power over what you do yourself—but increased knowledge, increased wealth, leisure are all increasing the domain in which responsibility is conceivable.”

We can say what we want about the tenets of a combination of Adlerian humanitarianism and Bohrian complementarity, but at least it’s an ethos. In fact, it’s our ethos—whether we like it or not. If we weren’t all Prometheans before the atomic age dawned, we most certainly are now. The heart of the matter is whether it’s an ethos we want.

We are not “the sum of our weaknesses and failures”; nor, apropos of this discussion of the “father of the atomic bomb,” are we the sum of our philosophical dependencies and intellectual idiosyncrasies. J. Robert Oppenheimer was a man whose prodigious scientific prowess had its complement in high ideals and a firm conscience. Together, these traits produced a belief system with the core tenets of responsibility and discipline. “But the rain fell and the floods came…”

The questions of “Responsibility for whom?” and “Discipline for what?” are unavoidable. The tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer is that his reach did not exceed his grasp, and his answers to those questions left him with resignation to what he called “our earthly privation and [the world’s] earthly horror.” He was a man of great faith, but his faith was predominantly set in princes, in projects and in power.

The epigraph to Johnson’s Modern Times—times upon which Oppenheimer exerted an influence of outsized magnitude—is from Psalm 2: “Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron; thou shalt dash them in pieces like a potter’s vessel. Be wise now, therefore, O ye kings: be instructed, ye judges of the earth.” This destructive image calls to mind Oppenheimer’s reference to John Donne’s Sonnet XIV from Holy Sonnets when dubbing the inaugural atomic test site “Trinity.” Sonnet XIV (a poem “I know and love,” Oppenheimer said) begins with these lines:

Batter my heart, three-person’d God, for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;

That I may rise and stand, o’erthrow me, and bend

Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

The power of these words is tangible: Donne’s variation on terms of destruction should leave us shaken upon reading or hearing them. I wonder if they shook Oppenheimer to the point of a reconsideration of his twofold belief in power as the basis for responsibility and in responsibility, dutifully maintained through the application of sensible discipline, as the foundation of the good life. He certainly believed things could be made new: considering the use of the atomic bombs to have wrought a fundamental change in the very nature of human existence, Oppenheimer called emphatically for “an enormous change in spirit” to reckon with this transformation. But I wonder if he ever wished himself to be made new, if he ever wished for a change, not “in spirit” generally speaking, but in his own spirit.

“There is no meaningful responsibility without power.” This may well be true. Power may indeed be the essential guarantee of meaningful responsibility, perhaps the guarantee also of meaningful, honorable living. But if it is, it is a power that first comes from above. “Power is made perfect in weakness.” We spiritual and moral beggars—weak, disenfranchised, impoverished—can avail ourselves of that power.

Did Robert Oppenheimer—for all the fire enkindled in his mind and his works—know that, albeit darkly? A line from his beloved Bhagavad-Gita reads: “Man is a creature whose substance is faith. What his faith is, he is.” The tragedy of the Promethean project—our project—is that it builds upon sand, instead of upon the Rock “who answers our doubtings” and makes all things new.

Credits: Odilon Redon, The Black Sun, c. 1900 (via Wikimedia Commons); U.S. Department of Energy, image of mushroom cloud of “Gadget” over Trinity test site, from Trinity and Beyond, 1995 (via Wikimedia Commons)